Landscape Architect on the Rise: Sara Zewde

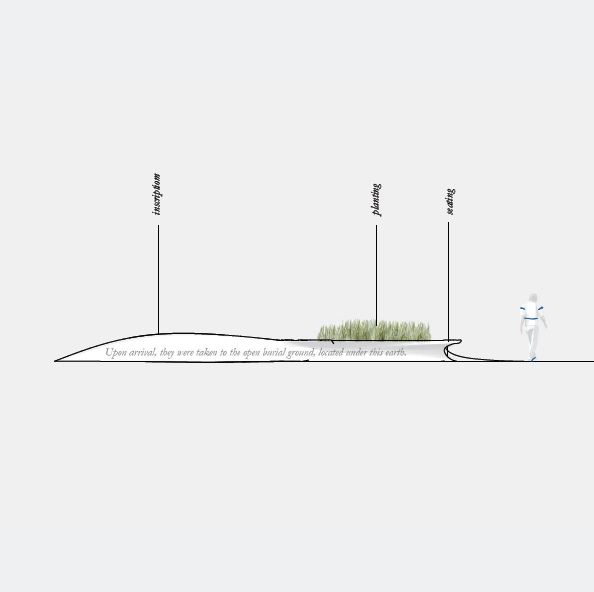

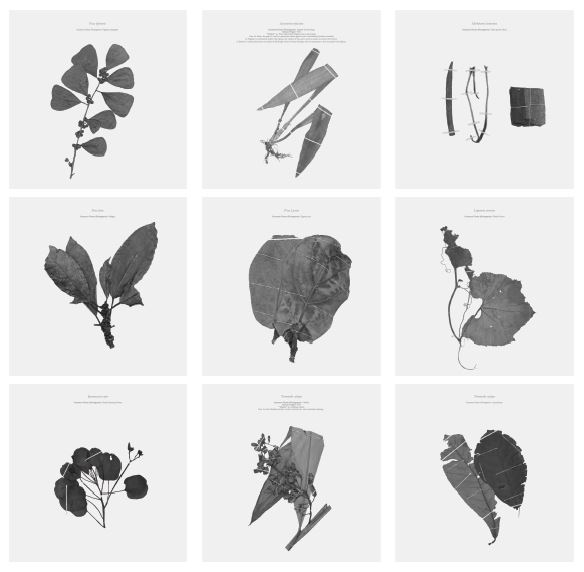

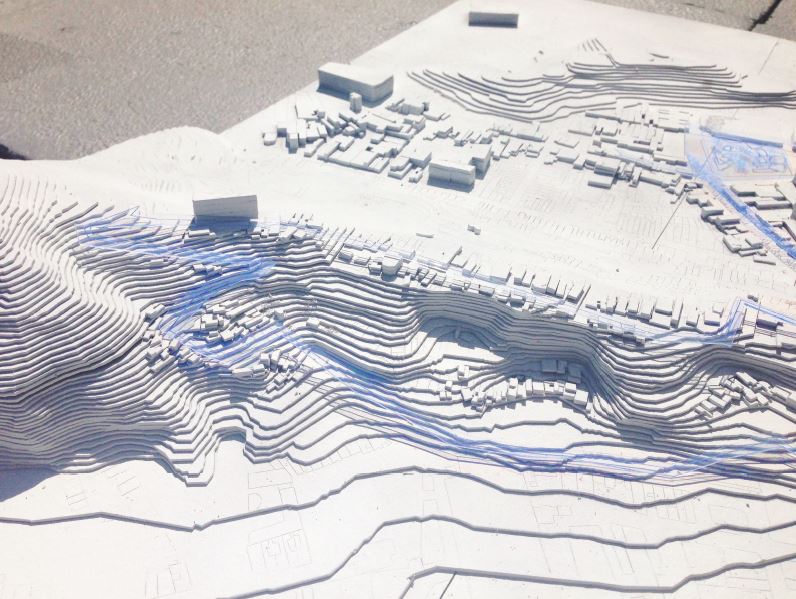

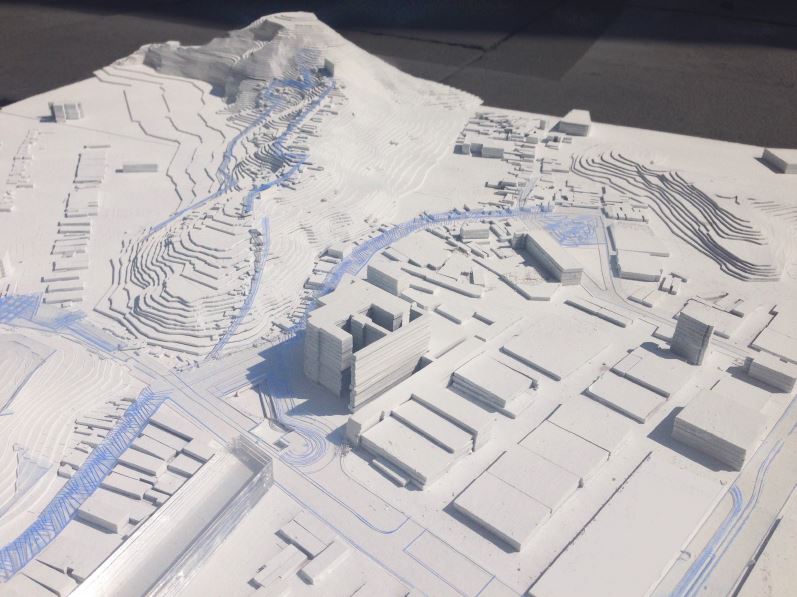

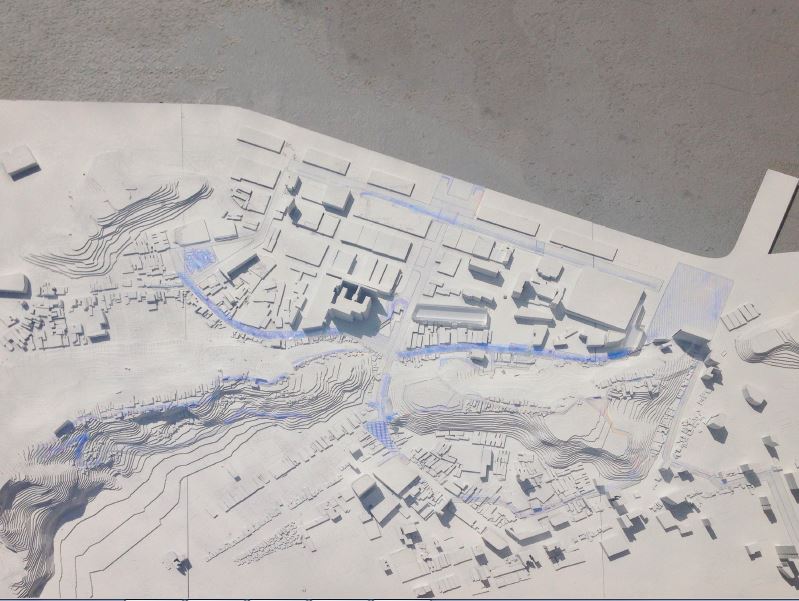

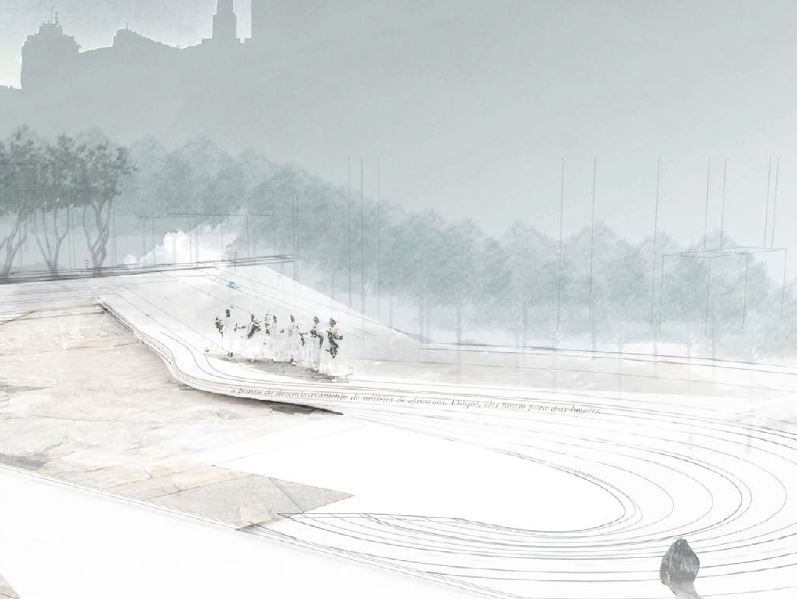

Photo courtesy of Sara Zewde. An interview with a young landscape architect about community outreach, urban renewal, and what it is like to meet Kanye West. Sara Zewde is no ordinary landscape architect. At 29, she has already worked internationally, holds a degree from MIT and Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), and was the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s 2014 Olmsted Scholar. Before entering Harvard, she began her career with a baptism of fire—leading a project that would have a major impact on culture in Brazil and define her life’s work. It was 2011, and Sara was working in Rio de Janeiro as a transportation trainer while the city was preparing for the 2016 Summer Olympics. She had recently graduated from MIT with a degree in urban planning and was planning to attend Harvard to study landscape architecture at the GSD. Many parts of the city were in the middle of a trendy makeover, including the Pequena Africa (Little Africa) neighborhood, a historic part of the city that is central to Black Brazilian history. The culturally-rich Little Africa neighborhood has traditionally suffered from neglect, and is now receiving a multi-billion dollar facelift, with plans for luxury condos and boutique amenities. However, the construction planners did not predict a major archaeological discovery; during one of the renovation projects, workers laying sewer lines found remains from the most infamous African slave port in the Americas, buried six feet beneath the street. Valongo Wharf, it was called, was the entryway for 22% of African slaves. Brazil, the last country to outlaw slavery in 1888, saw 40% of the Transatlantic slave trade. This discovery was monumental. It was a piece of the archaeological puzzle that the Black community had been missing. Sara, learning of the discovery, offered her skills as a designer to create a memorial for the port. Working day and night with funding from the Olmsted Scholarship, she created a design which reflects the spirit of the community. She captured movement with circular pathways, drawing inspiration from cultural traditions such as the Black Brazilian martial art of capoeira and samba music, which originated in the port neighborhood. Concrete ribbons guide visitors through the neighborhood, and exotic plant material evokes the African story. The plant choices boldly contrast guidelines in Brazil which state that some of the African plants are invasive. But Sara argued that the concept of “native plants” is defined by which species were present at the time of European settlement – a moment in time that is rather arbitrary in the evolution of plants. The African plant palette represents not only human movement, but movement of land: the plant choices pay homage to the ancient landmass of Pangea, when at one time, Brazil and Africa were connected. Sara chose African plants, such as the baobab tree, to replicate the landscapes that would have been familiar to the African slaves who entered the port.    Design proposal for Valongo Wharf. Images courtesy of Sara Zewde. If the paving-over of the Valongo Wharf is indicative of anything, the Black Brazilian community in Rio de Janeiro has a long way ahead of them to make sure that they secure the heritage site and Sara’s design comes to full fruition. It was this fascinating project that initially drew me to Sara’s work. As it turns out, Sara now works at Gustafson Guthrie Nichol in Seattle. Seizing this stroke of luck, I emailed her and we set a date to meet and chat. Also as it turns out, Sara is really easy to talk to. When we met for lunch, Sara quickly started talking about community outreach and about the methods used by landscape architects to gather community input and tell a story. In addition to working alongside community members in Rio de Janeiro, Sara has also worked on large-scale projects in New Orleans and Houston. She believes that landscape architects should be at the table meeting community members, but that they should also assert themselves as design professionals with abilities to make decisions that will enhance a community. Sara believes LAs should take the middle ground between gathering overly-exhaustive input in a community and making independent decisions without consulting stakeholders. Having a set of techniques is critical—she believes that LAs should be clear about what methods they use to interact with the community so that they can understand the story of that community and also use their time efficiently to convey design ideas. She mentions that these outreach methods haven’t evolved over the last sixty years since urban renewal, a time period from which architects and planners still carry a degree of guilt. She argues that we are still recovering from the mistakes of planning and design in the 50s and 60s—the highways dissecting communities, the housing projects, the landscapes built for cars. So maybe we overcompensate by spending too much of our time gathering community input to make up for the work of our predecessors, and then the project ends up in a bottleneck. She stresses that LAs should be able to draw a line and say, “Here are our skills and here’s our interpretation.”    Design proposal for Valongo Wharf. Images courtesy of Sara Zewde. After discussing community engagement, our conversation switched gears. When she asked why I reached out to her, I mentioned that I found her work when I was doing research for my last editor’s letter about diversity in landscape architecture. Sara often faces this situation, being a young, black woman in a very white profession. Imagine being asked to make presentations or give speeches because you look a certain way, or having people expect your work to reflect an experience of your entire race. “You’re put into a box,” she says. She describes the experience of being labeled as a “Black Landscape Architect,” and that people tend to focus on that. It can be hard to be seen simply as a designer. This is something that led her organization, the African-American Student Union (AASU) at the Harvard GSD, to reach out to artist and big-time celebrity Kanye West. Kanye, she explains, expressed the frustration of the public buying in to only certain roles for African-Americans. Even someone of his immense popularity struggles with being able to experiment with other professions or endeavors in art because of public criticism. This is the reason why her group reached out to the performer. When I ask what it was like meeting him, she laughs and says that he was very knowledgeable about architecture. Though he was only supposed to meet with her small group, he ended up visiting the studio, talking to students at their desks and asking about their work. Imagine being immersed in your work and having Kanye West pop by and ask you some questions about it. At the end of his visit, he gave a heartfelt speech on top of a desk to the entire GSD, and provided tickets for all of the students to see his concert in front-row seats. No doubt a memorable experience for the GSD.   Design proposal for Valongo Wharf. Images courtesy of Sara Zewde. My meeting with Sara has given me a lot to think about. It is empowering to have peers that have made such a large contribution to the profession and to communities. As landscape architects in a state known for being progressive, we can lead the way in creating creative and effective communication strategies that offer a balance between community needs and informed design. We have to be excellent listeners, and know when it’s time to tell the story. --Stephanie Stroud |